HAVE you ever lived in a village?

A village swims in gossip like a fish swims in water.

The Spanish have a saying about villagers: “They’ll talk about you, and if there’s nothing to say, they’ll invent it”.

This is the story of an Andalucian man – the mayor of his village – who hid in his own house from 1939 to 1969, and only his immediate family had any idea he was there!

There are two villages called “Mijas”: La Cala de Mijas (also called ‘Mijas Costa’) is a modern holiday development right on the beach, just outside Fuengirola.

Mijas Pueblo is a truly gorgeous little community, four miles away, up in the hills. Even today it has an isolated feel.

Manuel Cortés Quero (1906–1991) was the last Republican mayor of Mijas Pueblo between March 3, 1936, and November 23 of that same year.

First, a word about the “cacique”.

Originally, this was an Aztec term. The Spanish conquistadores in the Americas quickly learned that the most effective way to enslave the Indians was to ‘outsource’ the job – to an Indian!

Choose the most powerful, ruthless native and promise him a good life if he provided slaves, and hey presto – the ‘cacique’ did the Spaniards’ work for them.

READ MORE:

- Things you didn’t know about Spain’s famous Manchego cheese

- Hidden Corners of Spain: Salobreña is a must visit whether you are in Malaga or Granada

- Little-known Malaga: Michael Coy gives a brief rundown on some lesser known spots in the Andalucian city

This term was applied, in the 1930s, to any Spanish foreman who ran the local work force on behalf of the Fascists. The ‘cacique’ was a member of the community (with acolytes, of course) who bullied and killed the working people in Franco’s name.

Manolo Cortes was the village barber, and the mayor. In the 1930s Mijas was a solidly socialist village, where most adult men worked in agriculture.

When the civil war broke out in the summer of 1936, Manolo knew he had to ‘do his bit’. He said goodbye to his wife (Juliana) and his daughter (Maria) and went off to war.

He served the entire three years of the conflict on the Aragon Front.

The war ended in April 1939, and Manolo made his way back to his native province of Málaga. Travel wasn’t easy, especially for a defeated “leftie”, but he made it to Fuengirola, late one night.

In those days, motorised vehicles were almost unheard of in the villages. The only time you ever saw a car in Mijas was if someone was seriously ill and needed to be taken to hospital in Marbella.

But on this occasion Manolo was lucky. A truck driver in Fuengirola was delivering fish: he recognised the Mijas mayor and gave him a lift back to the village.

READ MORE:

“Are you mad?” asked Juliana, when he walked in after midnight. “If the cacique hears that you’re back, you’re a dead man.” She rattled off a list of men who had been ‘disposed of’ in Manolo’s absence.

There was nothing for it. He’d have to hide. He had no money to pay for travel. Juliana would say he’d been killed in Aragon.

And for 30 years, he lived in a walled-off cell inside his own house. The worst moment, he said, came one summer in the 1950s when a barbecue in the back yard got out of hand and set fire to the house.

(Luckily, the neighbours extinguished the blaze.)

In 1972, an English resident in Mijas, Ronald Fraser, published a book about Manolo’s ‘underground’ life. Entitled “In Hiding”, it’s available on Amazon.

Fraser interviewed Manolo and his family at length for the book.

Readers will agree with Fraser that Juliana is the true heroine of the story.

Not only did she bear the 30 years of the stress inevitable in fending-off questions about her husband, but she had, somehow, to make a living for all three – herself, Manolo and Maria.

She started by asking neighbours with hens to give her any spare eggs they might have. She walked 18 miles every day, there and back, to sell her eggs in Fuengirola and outlying farms.

Then she came home to Mijas to cook and clean.

Finally, in 1969, rumours started to circulate that Franco was thinking of an amnesty, pardoning ‘offenders’ from the civil war period.

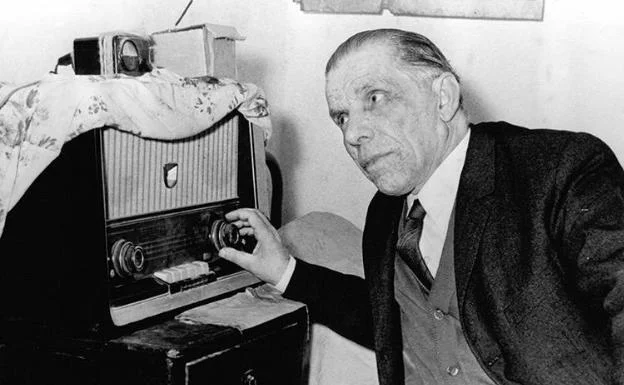

Manolo refused to come out – even though he’d heard it on the radio – until the amnesty was published in the official bulletin.

When, on March 28, 1969, he learned that the government had declared a statute of limitations, he decided to leave his confinement.

The then mayor of Mijas, Miguel González, accompanied him to the Málaga Guardia Civil Headquarters, where he was told what he had waited so many years to hear: “You are free.”